The lion (Panthera leo) is a large cat of the genus Panthera, native to Africa and India. It has a muscular, broad-chested body; a short, rounded head; round ears; and a dark, hairy tuft at the tip of its tail. It is sexually dimorphic; adult male lions are larger than females and have a prominent mane. It is a social species, forming groups called prides. A lion’s pride consists of a few adult males, related females, and cubs. Groups of female lions usually hunt together, preying mostly on medium-sized and large ungulates. The lion is an apex and keystone predator.

The lion inhabits grasslands, savannahs, and shrublands. It is usually more diurnal than other wild cats, but when persecuted, it adapts to being active at night and at twilight. During the Neolithic period, the lion ranged throughout Africa and Eurasia, from Southeast Europe to India, but it has been reduced to fragmented populations in sub-Saharan Africa and one population in western India. It has been listed as Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List since 1996 because populations in African countries have declined by about 43% since the early 1990s. Lion populations are untenable outside designated protected areas. Although the cause of the decline is not fully understood, habitat loss and conflicts with humans are the greatest causes for concern.

One of the most widely recognised animal symbols in human culture, the lion has been extensively depicted in sculptures and paintings, on national flags, and in literature and films. Lions have been kept in menageries since the time of the Roman Empire and have been a key species sought for exhibition in zoological gardens across the world since the late 18th century. Cultural depictions of lions have occurred worldwide, particularly as a symbol of power and royalty.

Etymology

The English word lion is derived via Anglo-Norman liun from Latin leōnem (nominative: leō), which in turn was a borrowing from Ancient Greek λέων léōn. The Hebrew word לָבִיא lavi may also be related.[4] The generic name Panthera is traceable to the classical Latin word ‘panthēra’ and the ancient Greek word πάνθηρ ‘panther’.[5]

Taxonomy

Felis leo was the scientific name used by Carl Linnaeus in 1758, who described the lion in his work Systema Naturae.[3] The genus name Panthera was coined by Lorenz Oken in 1816.[10] Between the mid-18th and mid-20th centuries, 26 lion specimens were described and proposed as subspecies, of which 11 were recognised as valid in 2005.[1] They were distinguished mostly by the size and colour of their manes and skins.[11]

Subspecies

In the 19th and 20th centuries, several lion type specimens were described and proposed as subspecies, with about a dozen recognised as valid taxa until 2017.[1] Between 2008 and 2016, IUCN Red List assessors used only two subspecific names: P. l. leo for African lion populations, and P. l. persica for the Asiatic lion population.[2][12][13] In 2017, the Cat Classification Task Force of the Cat Specialist Group revised lion taxonomy, and recognises two subspecies based on results of several phylogeographic studies on lion evolution, namely:[14]

- P. l. leo (Linnaeus, 1758) − the nominate lion subspecies includes the Asiatic lion, the regionally extinct Barbary lion, and lion populations in West and northern parts of Central Africa.[14] Synonyms include P. l. persica (Meyer, 1826), P. l. senegalensis (Meyer, 1826), P. l. kamptzi (Matschie, 1900), and P. l. azandica (Allen, 1924).[1] Multiple authors referred to it as ‘northern lion’ and ‘northern subspecies’.[15][16]

- P. l. melanochaita (Smith, 1842) − includes the extinct Cape lion and lion populations in East and Southern African regions.[14] Synonyms include P. l. somaliensis (Noack 1891), P. l. massaica (Neumann, 1900), P. l. sabakiensis (Lönnberg, 1910), P. l. bleyenberghi (Lönnberg, 1914), P. l. roosevelti (Heller, 1914), P. l. nyanzae (Heller, 1914), P. l. hollisteri (Allen, 1924), P. l. krugeri (Roberts, 1929), P. l. vernayi (Roberts, 1948), and P. l. webbiensis (Zukowsky, 1964).[1][11] It has been referred to as ‘southern subspecies’ and ‘southern lion’.[16]

However, there seems to be some degree of overlap between both groups in northern Central Africa. DNA analysis from a more recent study indicates that Central African lions are derived from both northern and southern lions, as they cluster with P. leo leo in mtDNA-based phylogenies whereas their genomic DNA indicates a closer relationship with P. leo melanochaita.[17]

Lion samples from some parts of the Ethiopian Highlands cluster genetically with those from Cameroon and Chad, while lions from other areas of Ethiopia cluster with samples from East Africa. Researchers, therefore, assume Ethiopia is a contact zone between the two subspecies.[18] Genome-wide data of a wild-born historical lion sample from Sudan showed that it clustered with P. l. leo in mtDNA-based phylogenies, but with a high affinity to P. l. melanochaita. This result suggested that the taxonomic position of lions in Central Africa may require revision.[19]

Fossil records

Other lion subspecies or sister species to the modern lion existed in prehistoric times:[20]

- P. l. sinhaleyus was a fossil carnassial excavated in Sri Lanka, which was attributed to a lion. It is thought to have become extinct around 39,000 years ago.[21]

- P. fossilis was larger than the modern lion and lived in the Middle Pleistocene. Bone fragments were excavated in caves in the United Kingdom, Germany, Italy and Czech Republic.[22][23]

- P. spelaea, or the cave lion, lived in Eurasia and Beringia during the Late Pleistocene. It became extinct due to climate warming or human expansion latest by 11,900 years ago.[24] Bone fragments excavated in European, North Asian, Canadian and Alaskan caves indicate that it ranged from Europe across Siberia into western Alaska.[25] It likely derived from P. fossilis,[26] and was genetically isolated and highly distinct from the modern lion in Africa and Eurasia.[27][26] It is depicted in Paleolithic cave paintings, ivory carvings, and clay busts.[28]

- P. atrox, or the American lion, ranged in the Americas from Canada to possibly Patagonia during the Late Pleistocene.[29] It diverged from the cave lion around 165,000 years ago.[30] A fossil from Edmonton dates to 11,355 ± 55 years ago.[31]

Evolution

Skull of an American lion on display at the National Museum of Natural History

red Panthera spelaea

blue Panthera atrox

green Panthera leo

Maximal range of the modern lion

and its prehistoric relatives

in the late Pleistocene

The Panthera lineage is estimated to have genetically diverged from the common ancestor of the Felidae around 9.32 to 4.47 million years ago to 11.75 to 0.97 million years ago.[6][32][33] Results of analyses differ in the phylogenetic relationship of the lion; it was thought to form a sister group with the jaguar that diverged 3.46 to 1.22 million years ago,[6] but also with the leopard that diverged 3.1 to 1.95 million years ago[8][9] to 4.32 to 0.02 million years ago. Hybridisation between lion and snow leopard ancestors possibly continued until about 2.1 million years ago.[33] The lion-leopard clade was distributed in the Asian and African Palearctic since at least the early Pliocene.[34] The earliest fossils recognisable as lions were found at Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania and are estimated to be up to 2 million years old.[32]

Estimates for the divergence time of the modern and cave lion lineages range from 529,000 to 392,000 years ago based on mutation rate per generation time of the modern lion. There is no evidence for gene flow between the two lineages, indicating that they did not share the same geographic area.[19] The Eurasian and American cave lions became extinct at the end of the last glacial period without mitochondrial descendants on other continents.[27][35][36] The modern lion was probably widely distributed in Africa during the Middle Pleistocene and started to diverge in sub-Saharan Africa during the Late Pleistocene. Lion populations in East and Southern Africa became separated from populations in West and North Africa when the equatorial rainforest expanded 183,500 to 81,800 years ago.[37] They shared a common ancestor probably between 98,000 and 52,000 years ago.[19] Due to the expansion of the Sahara between 83,100 and 26,600 years ago, lion populations in West and North Africa became separated. As the rainforest decreased and thus gave rise to more open habitats, lions moved from West to Central Africa. Lions from North Africa dispersed to southern Europe and Asia between 38,800 and 8,300 years ago.[37]

Extinction of lions in southern Europe, North Africa and the Middle East interrupted gene flow between lion populations in Asia and Africa. Genetic evidence revealed numerous mutations in lion samples from East and Southern Africa, which indicates that this group has a longer evolutionary history than genetically less diverse lion samples from Asia and West and Central Africa.[38] A whole genome-wide sequence of lion samples showed that samples from West Africa shared alleles with samples from Southern Africa, and samples from Central Africa shared alleles with samples from Asia. This phenomenon indicates that Central Africa was a melting pot of lion populations after they had become isolated, possibly migrating through corridors in the Nile Basin during the early Holocene.[19]

Hybrids

Further information: Panthera hybrid

In zoos, lions have been bred with tigers to create hybrids for the curiosity of visitors or for scientific purpose.[39][40] The liger is bigger than a lion and a tiger, whereas most tigons are relatively small compared to their parents because of reciprocal gene effects.[41][42] The leopon is a hybrid between a lion and leopard.[43]

Description

A tuft at the end of the tail is a distinct characteristic of the lion.

Skeleton

The lion is a muscular, broad-chested cat with a short, rounded head, a reduced neck, and round ears; males have broader heads. The fur varies in colour from light buff to silvery grey, yellowish red, and dark brown. The colours of the underparts are generally lighter. A new-born lion has dark spots, which fade as the cub reaches adulthood, although faint spots may still be seen on the legs and underparts.[44][45] The tail of all lions ends in a dark, hairy tuft that, in some lions, conceals an approximately 5 mm (0.20 in)-long, hard “spine” or “spur” composed of dermal papillae.[46] The functions of the spur are unknown. The tuft is absent at birth and develops at around 5+1⁄2 months of age. It is readily identifiable at the age of seven months.[47]

Its skull is very similar to that of the tiger, although the frontal region is usually more depressed and flattened and has a slightly shorter postorbital region and broader nasal openings than those of the tiger. Due to the amount of skull variation in the two species, usually only the structure of the lower jaw can be used as a reliable indicator of species.[48][49]

The skeletal muscles of the lion make up 58.8% of its body weight and represent the highest percentage of muscles among mammals.[50][51] The lion has a high concentration of fast twitch muscle fibres, giving them quick bursts of speed but less stamina.[52][53]

Size

Among felids, the lion is second only to the tiger in size.[45] The size and weight of adult lions vary across its range and habitats.[54][55][56][57] Accounts of a few individuals that were larger than average exist from Africa and India.[44][58][59][60]

| Average | Female lions | Male lions |

|---|---|---|

| Head-and-body length | 160–184 cm (63–72 in)[61] | 184–208 cm (72–82 in)[61] |

| Tail length | 72–89.5 cm (28.3–35.2 in)[61] | 82.5–93.5 cm (32.5–36.8 in)[61] |

| Weight | 118.37–143.52 kg (261.0–316.4 lb) in Southern Africa,[54] 119.5 kg (263 lb) in East Africa,[54] 110–120 kg (240–260 lb) in India[55] | 186.55–225 kg (411.3–496.0 lb) in Southern Africa,[54] 174.9 kg (386 lb) in East Africa,[54] 160–190 kg (350–420 lb) in India[55] |

Mane

A six-year-old male in Phinda Private Game Reserve

Young male in Pendjari National Park

The male lion’s mane is the most recognisable feature of the species.[11] It may have evolved around 320,000–190,000 years ago.[62] It grows downwards and backwards, covering most of the head, neck, shoulders, and chest. The mane is typically brownish and tinged with yellow, rust, and black hairs.[45] Mutations in the genes microphthalmia-associated transcription factor and tyrosinase are possibly responsible for the colour of manes.[63][64] It starts growing when lions enter adolescence, when testosterone levels increase, and reach their full size at around four years old.[65] Cool ambient temperatures in European and North American zoos may result in a heavier mane.[66] On average, Asiatic lions have sparser manes than African lions.[67]

This feature likely evolved to signal the fitness of males to females. Males with darker manes appear to have greater reproductive success and are more likely to remain in a pride for longer. They have longer and thicker hair and higher testosterone levels, but they are also more vulnerable to heat stress.[68][69] The core body temperature does apparently not increase regardless of sex, season, feeding time, length and colour of mane, but only surface temperature is affected.[70] Unlike in other felid species, female lions consistently interact with multiple males at once.[71] Another hypothesis suggests that the mane also serves to protect the neck in fights, but this is disputed.[72][73] During fights, including those involving maneless females and adolescents, the neck is not targeted as much as the face, back, and hindquarters. Injured lions also begin to lose their manes.[74]

Almost all male lions in Pendjari National Park are either maneless or have very short manes.[75] Maneless lions have also been reported in Senegal, in Sudan‘s Dinder National Park and in Tsavo East National Park, Kenya.[76] Castrated lions often have little to no mane because the removal of the gonads inhibits testosterone production.[77] Rarely, both wild and captive lionesses have manes.[78][79] Increased testosterone may be the cause of maned lionesses reported in northern Botswana.[80]

Colour variation

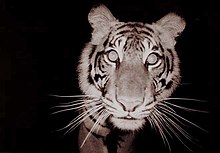

Further information: White lion

The white lion is a rare morph with a genetic condition called leucism, which is caused by a double recessive allele. It is not albino; it has normal pigmentation in the eyes and skin. White lions have occasionally been encountered in and around Kruger National Park and the adjacent Timbavati Private Game Reserve in eastern South Africa. They were removed from the wild in the 1970s, thus decreasing the white lion gene pool. Nevertheless, 17 births have been recorded in five prides between 2007 and 2015.[81] White lions are selected for breeding in captivity.[82] They have reportedly been bred in camps in South Africa for use as trophies to be killed during canned hunts.[83]

Distribution and habitat

African lions live in scattered populations across sub-Saharan Africa. The lion prefers grassy plains and savannahs, scrub bordering rivers, and open woodlands with bushes. It rarely enters closed forests. On Mount Elgon, the lion has been recorded up to an elevation of 3,600 m (11,800 ft) and close to the snow line on Mount Kenya.[44] Savannahs with an annual rainfall of 300 to 1,500 mm (12 to 59 in) make up the majority of lion habitat in Africa, estimated at 3,390,821 km2 (1,309,203 sq mi) at most, but remnant populations are also present in tropical moist forests in West Africa and montane forests in East Africa.[84] The Asiatic lion now survives only in and around Gir National Park in Gujarat, western India. Its habitat is a mixture of dry savannah forest and very dry, deciduous scrub forest.[12]

Historical range

In Africa, the range of the lion originally spanned most of the central African rainforest zone and the Sahara desert.[85] In the 1960s, it became extinct in North Africa, except in the southern part of Sudan.[86][84][87]

During the mid-Holocene, around 8,000-6,000 years ago, the range of lions expanded into Southeastern and Eastern Europe, partially re-occupying the range of the now extinct cave lion.[88] In Hungary, the modern lion was present from about 4,500 to 3,200 years Before Present.[89] In Ukraine, the modern lion was present from about 6,400 to 2,000 years Before Present.[88] In Greece, it was common, as reported by Herodotus in 480 BC; it was considered rare by 300 BC and extirpated by AD 100.[44]

In Asia the lion once ranged in regions where climatic conditions supported an abundance of prey.[90] It was present in the Caucasus until the 10th century.[49] It lived in the Levant until the Middle Ages and in Southwest Asia until the late 19th century. By the late 19th century, it had been extirpated in most of Turkey.[91] The last live lion in Iran was sighted in 1942, about 65 km (40 mi) northwest of Dezful,[92] although the corpse of a lioness was found on the banks of the Karun river in Khuzestan province in 1944.[93] It once ranged from Sind and Punjab in Pakistan to Bengal and the Narmada River in central India.[94]

Behaviour and ecology

Lions spend much of their time resting; they are inactive for about twenty hours per day.[95] Although lions can be active at any time, their activity generally peaks after dusk with a period of socialising, grooming, and defecating. Intermittent bursts of activity continue until dawn, when hunting most often takes place. They spend an average of two hours a day walking and fifty minutes eating.[96]

Group organisation

Lion pride in Etosha National Park

A lioness (left) and two males in Masai Mara

The lion is the most social of all wild felid species, living in groups of related individuals with their offspring. Such a group is called a “pride“. Groups of male lions are called “coalitions”.[97] Females form the stable social unit in a pride and do not tolerate outside females.[98] The majority of females remain in their birth prides while all males and some females will disperse.[99] The average pride consists of around 15 lions, including several adult females and up to four males and their cubs of both sexes. Large prides, consisting of up to 30 individuals, have been observed.[100] The sole exception to this pattern is the Tsavo lion pride that always has just one adult male.[101] Prides act as fission–fusion societies, and members will split into subgroups that keep in contact with roars.[102]

Nomadic lions range widely and move around sporadically, either in pairs or alone.[97] Pairs are more frequent among related males. A lion may switch lifestyles; nomads can become residents and vice versa.[103] Interactions between prides and nomads tend to be hostile, although pride females in estrus allow nomadic males to approach them.[104] Males spend years in a nomadic phase before gaining residence in a pride.[105] A study undertaken in the Serengeti National Park revealed that nomadic coalitions gain residency at between 3.5 and 7.3 years of age.[106] In Kruger National Park, dispersing male lions move more than 25 km (16 mi) away from their natal pride in search of their own territory. Female lions stay closer to their natal pride. Therefore, female lions in an area are more closely related to each other than male lions in the same area.[107]

The evolution of sociability in lions was likely driven both by high population density and the clumped resources of savannah habitats. The larger the pride, the more high-quality territory they can defend; “hotspots” being near river confluences, where the cats have better access to water, prey and shelter (via vegetation).[108][109] The area occupied by a pride is called a “pride area” whereas that occupied by a nomad is a “range”.[97] Males associated with a pride patrol the fringes.[45] Both males and females defend the pride against intruders, but the male lion is better-suited for this purpose due to its stockier, more powerful build. Some individuals consistently lead the defence against intruders, while others lag behind.[110] Lions tend to assume specific roles in the pride; slower-moving individuals may provide other valuable services to the group.[111] Alternatively, there may be rewards associated with being a leader that fends off intruders; the rank of lionesses in the pride is reflected in these responses.[112] The male or males associated with the pride must defend their relationship with the pride from outside males who may attempt to usurp them.[103] Dominance hierarchies do not appear to exist among individuals of either sex in a pride.[113]

Asiatic lion prides differ in group composition. Male Asiatic lions are solitary or associate with up to three males, forming a loose pride while females associate with up to 12 other females, forming a stronger pride together with their cubs. Female and male lions associate only when mating.[114] Coalitions of males hold territory for a longer time than single lions. Males in coalitions of three or four individuals exhibit a pronounced hierarchy, in which one male dominates the others and mates more frequently.[115]

Hunting and diet

A skeletal mount of a lion attacking a common eland, on display at The Museum of Osteology

Four lionesses catching a buffalo in the Serengeti

Lions feeding on a zebra

The lion is a generalist hypercarnivore and is considered to be both an apex and keystone predator due to its wide prey spectrum.[116][117] Its prey consists mainly of medium-sized to large ungulates, particularly blue wildebeest, plains zebra, African buffalo, gemsbok and giraffe. It also frequently takes common warthog despite it being much smaller.[118] In India, chital and sambar deer are the most common wild prey,[45][118][119] while livestock contributes significantly to lion kills outside protected areas.[120] It usually avoids fully grown adult elephants, rhinoceros and hippopotamus and small prey like dik-dik, hyraxes, hares and monkeys. Unusual prey include porcupines and small reptiles. Lions kill other predators but seldom consume them.[121]

Young lions first display stalking behaviour at around three months of age, although they do not participate in hunting until they are almost a year old and begin to hunt effectively when nearing the age of two.[122] Single lions are capable of bringing down zebra and wildebeest, while larger prey like buffalo and giraffe are riskier.[103] In Chobe National Park, large prides have been observed hunting African bush elephants up to around 15 years old in exceptional cases, with the victims being calves, juveniles, and even subadults.[123][124] In typical group hunts, each lioness has a favoured position in the group, either stalking prey on the “wing”, then attacking, or moving a smaller distance in the centre of the group and capturing prey fleeing from other lionesses. Males attached to prides do not usually participate in group hunting.[125] Some evidence suggests, however, that males are just as successful as females; they are typically solo hunters who ambush prey in small bushland.[126] They may join in the hunting of large, slower-moving prey like buffalo; and even hunt them on their own. Moderately-sized hunting groups generally have higher success rates than lone females and larger groups.[127]

Lions are not particularly known for their stamina. For instance, a lioness’s heart comprises only 0.57% of her body weight and a male’s is about 0.45% of his body weight, whereas a hyena’s heart comprises almost 1% of its body weight.[128] Thus, lions run quickly only in short bursts at about 48–59 km/h (30–37 mph) and need to be close to their prey before starting the attack.[129] They take advantage of factors that reduce visibility; many kills take place near some form of cover or at night.[130] One study in 2018 recorded a lion running at a top speed of 74.1 km/h (46.0 mph).[131] The lion accelerates at the start of the chase by 9.5 m/s (34 km/h; 21 mph), whereas zebras, wildebeest and Thomson’s gazelle accelerate by 5 m/s (18 km/h; 11 mph), 5.6 m/s (20 km/h; 13 mph) and 4.5 m/s (16 km/h; 10 mph) respectively; acceleration appears to be more important than steady displacement speed in lion hunts.[132] The lion’s attack is short and powerful; it attempts to catch prey with a fast rush and final leap, usually pulls it down by the rump, and kills with a clamping bite to the throat or muzzle. It can hold the prey’s throat for up to 13 minutes, until the prey stops moving.[133] It has a bite force from 1593.8 to 1768 Newtons at the canine tip and up 4167.6 Newtons at the carnassial notch.[134][135][136]

Lions typically consume prey at the location of the hunt but sometimes drag large prey into cover.[137] They tend to squabble over kills, particularly the males. Cubs suffer most when food is scarce but otherwise all pride members eat their fill, including old and crippled lions, which can live on leftovers.[103] Large kills are shared more widely among pride members.[138] An adult lioness requires an average of about 5 kg (11 lb) of meat per day while males require about 7 kg (15 lb).[139] Lions gorge themselves and eat up to 30 kg (66 lb) in one session.[93] If it is unable to consume all of the kill, it rests for a few hours before continuing to eat. On hot days, the pride retreats to shade with one or two males standing guard.[137] Lions defend their kills from scavengers such as vultures and hyenas.[103]

Lions scavenge on carrion when the opportunity arises, scavenging animals dead from natural causes such as disease or those that were killed by other predators. Scavenging lions keep a constant lookout for circling vultures, which indicate the death or distress of an animal.[140] Most carrion on which both hyenas and lions feed upon are killed by hyenas rather than lions.[57] Carrion is thought to provide a large part of lion diet.[141]

Predatory competition

Lioness chasing a spotted hyena in Kruger National Park

Lioness stealing a kill from a leopard in Kruger National Park

Lions and spotted hyenas occupy a similar ecological niche and compete for prey and carrion; a review of data across several studies indicates a dietary overlap of 58.6%.[142] Lions typically ignore hyenas unless they are on a kill or are being harassed, while the latter tend to visibly react to the presence of lions with or without the presence of food. In the Ngorongoro crater, lions subsist largely on kills stolen from hyenas, causing them to increase their kill rate.[143] In Botswana’s Chobe National Park, the situation is reversed as hyenas there frequently challenge lions and steal their kills, obtaining food from 63% of all lion kills.[144] When confronted on a kill, hyenas may either leave or wait patiently at a distance of 30–100 m (98–328 ft) until the lions have finished.[145] Hyenas may feed alongside lions and force them off a kill. The two species attack one another even when there is no food involved for no apparent reason.[146] Lions can account for up to 71% of hyena deaths in Etosha National Park. Hyenas have adapted by frequently mobbing lions that enter their home ranges.[147] When the lion population in Kenya’s Masai Mara National Reserve declined, the spotted hyena population increased rapidly.[148]

Lions tend to dominate cheetahs and leopards, steal their kills and kill their cubs and even adults when given the chance.[149] Cheetahs often lose their kills to lions or other predators.[150] A study in the Serengeti ecosystem revealed that lions killed at least 17 of 125 cheetah cubs born between 1987 and 1990.[151] Cheetahs avoid their competitors by hunting at different times and habitats.[152] Leopards, by contrast, do not appear to be motivated by an avoidance of lions, as they use heavy vegetation regardless of whether lions are present in an area and both cats are active around the same time of day. In addition, there is no evidence that lions affect leopard abundance.[153] Leopards take refuge in trees, though lionesses occasionally attempt to climb up and retrieve their kills.[154]

Lions similarly dominate African wild dogs, taking their kills and dispatching pups or adult dogs. Population densities of wild dogs are low in areas where lions are more abundant.[155] However, there are a few reported cases of old and wounded lions falling prey to wild dogs.[156][157]

Reproduction and life cycle

Lions mating at Masai Mara

A lion cub in Masai Mara

Most lionesses reproduce by the time they are four years of age.[158] Lions do not mate at a specific time of year and the females are polyestrous.[159] Like those of other cats, the male lion’s penis has spines that point backward. During withdrawal of the penis, the spines rake the walls of the female’s vagina, which may cause ovulation.[160][161] A lioness may mate with more than one male when she is in heat.[162] Lions of both sexes may be involved in group homosexual and courtship activities. Males will also head-rub and roll around with each other before mounting each other.[163][164] Generation length of the lion is about seven years.[165] The average gestation period is around 110 days;[159] the female gives birth to a litter of between one and four cubs in a secluded den, which may be a thicket, a reed-bed, a cave, or some other sheltered area, usually away from the pride. She will often hunt alone while the cubs are still helpless, staying relatively close to the den.[166] Lion cubs are born blind, their eyes opening around seven days after birth. They weigh 1.2–2.1 kg (2.6–4.6 lb) at birth and are almost helpless, beginning to crawl a day or two after birth and walking around three weeks of age.[167] To avoid a buildup of scent attracting the attention of predators, the lioness moves her cubs to a new den site several times a month, carrying them one-by-one by the nape of the neck.[166]

Usually, the mother does not integrate herself and her cubs back into the pride until the cubs are six to eight weeks old.[166] Sometimes the introduction to pride life occurs earlier, particularly if other lionesses have given birth at about the same time.[103][168] When first introduced to the rest of the pride, lion cubs lack confidence when confronted with adults other than their mother. They soon begin to immerse themselves in the pride life, however, playing among themselves or attempting to initiate play with the adults.[168] Lionesses with cubs of their own are more likely to be tolerant of another lioness’s cubs than lionesses without cubs. Male tolerance of the cubs varies—one male could patiently let the cubs play with his tail or his mane, while another may snarl and bat the cubs away.[169]Video of a lioness and her cubs in Phinda Reserve

Pride lionesses often synchronise their reproductive cycles and communal rearing and suckling of the young, which suckle indiscriminately from any or all of the nursing females in the pride. The synchronisation of births is advantageous because the cubs grow to being roughly the same size and have an equal chance of survival, and sucklings are not dominated by older cubs.[103][168] Weaning occurs after six or seven months. Male lions reach maturity at about three years of age and at four to five years are capable of challenging and displacing adult males associated with another pride. They begin to age and weaken at between 10 and 15 years of age at the latest.[170]

When one or more new males oust the previous males associated with a pride, the victors often kill any existing young cubs, perhaps because females do not become fertile and receptive until their cubs mature or die. Females often fiercely defend their cubs from a usurping male but are rarely successful unless a group of three or four mothers within a pride join forces against the male.[171] Cubs also die from starvation and abandonment, and predation by leopards, hyenas and wild dogs. Male cubs are excluded from their maternal pride when they reach maturity at around two or three years of age,[172] while some females may leave when they reach the age of two.[99] When a new male lion takes over a pride, adolescents both male and female may be evicted.[173]

Health and mortality

Lions may live 12–17 years in the wild.[45] Although adult lions have no natural predators, evidence suggests most die violently from attacks by humans or other lions.[174] Lions often inflict serious injuries on members of other prides they encounter in territorial disputes or members of the home pride when fighting at a kill.[175] Crippled lions and cubs may fall victim to hyenas and leopards or be trampled by buffalo or elephants. Careless lions may be maimed when hunting prey.[176] Nile crocodiles may also kill and eat lions, evidenced by the occasional lion claw found in crocodile stomachs.[177]

Ticks commonly infest the ears, neck and groin regions of the lions.[178][179] Adult forms of several tapeworm species of the genus Taenia have been isolated from lion intestines, having been ingested as larvae in antelope meat.[180] Lions in the Ngorongoro Crater were afflicted by an outbreak of stable fly (Stomoxys calcitrans) in 1962, resulting in lions becoming emaciated and covered in bloody, bare patches. Lions sought unsuccessfully to evade the biting flies by climbing trees or crawling into hyena burrows; many died or migrated and the local population dropped from 70 to 15 individuals.[181] A more recent outbreak in 2001 killed six lions.[182]

Captive lions have been infected with canine distemper virus (CDV) since at least the mid-1970s.[183] CDV is spread by domestic dogs and other carnivores; a 1994 outbreak in Serengeti National Park resulted in many lions developing neurological symptoms such as seizures. During the outbreak, several lions died from pneumonia and encephalitis.[184] Feline immunodeficiency virus and lentivirus also affect captive lions.[185][186]

Communication

Head rubbing among pride members is a common social behaviour.

A male lion raises his tail while marking his territory.

When resting, lion socialisation occurs through a number of behaviours; the animal’s expressive movements are highly developed. The most common peaceful, tactile gestures are head rubbing and social licking,[187] which have been compared with the role of allogrooming among primates.[188] Head rubbing, nuzzling the forehead, face and neck against another lion appears to be a form of greeting[189] and is seen often after an animal has been apart from others or after a fight or confrontation. Males tend to rub other males, while cubs and females rub females.[190] Social licking often occurs in tandem with head rubbing; it is generally mutual and the recipient appears to express pleasure. The head and neck are the most common parts of the body licked; this behaviour may have arisen out of utility because lions cannot lick these areas themselves.[191]

A captive lion roaring

Problems playing this file? See media help.

Lions have an array of facial expressions and body postures that serve as visual gestures.[192] A common facial expression is the “grimace face” or flehmen response, which a lion makes when sniffing chemical signals and involves an open mouth with bared teeth, raised muzzle, wrinkled nose, closed eyes and relaxed ears.[193] Lions also use chemical and visual marking;[192] males spray urine[194][195] and scrape plots of ground and objects within the territory.[192]

The lion’s repertoire of vocalisations is large; variations in intensity and pitch appear to be central to communication. Most lion vocalisations are variations of growling, snarling, meowing and roaring. Other sounds produced include puffing, bleating and humming. Roaring is used to advertise its presence. Lions most often roar at night, a sound that can be heard from a distance of 8 kilometres (5 mi).[196] They tend to roar in a very characteristic manner starting with a few deep, long roars that subside into grunts.[197][198]

Conservation

The lion is listed as Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List. The Indian population is listed on CITES Appendix I and the African population on CITES Appendix II.[2]

In Africa

Several large and well-managed protected areas in Africa host large lion populations. Where an infrastructure for wildlife tourism has been developed, cash revenue for park management and local communities is a strong incentive for lion conservation.[2] Most lions now live in East and Southern Africa; their numbers are rapidly decreasing, and fell by an estimated 30–50% in the late half of the 20th century. Primary causes of the decline include disease and human interference.[2] In 1975, it was estimated that since the 1950s, lion numbers had decreased by half to 200,000 or fewer.[199] Estimates of the African lion population range between 16,500 and 47,000 living in the wild in 2002–2004.[200][86]

In the Republic of the Congo, Odzala-Kokoua National Park was considered a lion stronghold in the 1990s. By 2014, no lions were recorded in the protected area so the population is considered locally extinct.[201] The West African lion population is isolated from the one in Central Africa, with little or no exchange of breeding individuals. In 2015, it was estimated that this population consists of about 400 animals, including fewer than 250 mature individuals. They persist in three protected areas in the region, mostly in one population in the W A P protected area complex, shared by Benin, Burkina Faso and Niger. This population is listed as Critically Endangered.[13] Field surveys in the WAP ecosystem revealed that lion occupancy is lowest in the W National Park, and higher in areas with permanent staff and thus better protection.[202]

A population occurs in Cameroon’s Waza National Park, where between approximately 14 and 21 animals persisted as of 2009.[203] In addition, 50 to 150 lions are estimated to be present in Burkina Faso’s Arly-Singou ecosystem.[204] In 2015, an adult male lion and a female lion were sighted in Ghana’s Mole National Park. These were the first sightings of lions in the country in 39 years.[205] In the same year, a population of up to 200 lions that was previously thought to have been extirpated was filmed in the Alatash National Park, Ethiopia, close to the Sudanese border.[206][207]

In 2005, Lion Conservation Strategies were developed for West and Central Africa, and or East and Southern Africa. The strategies seek to maintain suitable habitat, ensure a sufficient wild prey base for lions, reduce factors that lead to further fragmentation of populations, and make lion–human coexistence sustainable.[208][209] Lion depredation on livestock is significantly reduced in areas where herders keep livestock in improved enclosures. Such measures contribute to mitigating human–lion conflict.[210]

In Asia

The last refuge of the Asiatic lion population is the 1,412 km2 (545 sq mi) Gir National Park and surrounding areas in the region of Saurashtra or Kathiawar Peninsula in Gujarat State, India. The population has risen from approximately 180 lions in 1974 to about 400 in 2010.[211] It is geographically isolated, which can lead to inbreeding and reduced genetic diversity. Since 2008, the Asiatic lion has been listed as Endangered on the IUCN Red List.[12] By 2015, the population had grown to 523 individuals inhabiting an area of 7,000 km2 (2,700 sq mi) in Saurashtra.[212][213][214] In 2017, about 650 individuals were recorded during the Asiatic Lion Census.[215]

The presence of numerous human settlements close to Gir National Park resulted in conflict between lions, local people and their livestock.[216][212] Some consider the presence of lions a benefit, as they keep populations of crop damaging herbivores in check.[217]

Captive breeding

Lions imported to Europe before the middle of the 19th century were possibly foremost Barbary lions from North Africa, or Cape lions from Southern Africa.[218] Another 11 animals thought to be Barbary lions kept in Addis Ababa Zoo are descendants of animals owned by Emperor Haile Selassie. WildLink International in collaboration with Oxford University launched an ambitious International Barbary Lion Project with the aim of identifying and breeding Barbary lions in captivity for eventual reintroduction into a national park in the Atlas Mountains of Morocco.[219] However, a genetic analysis showed that the captive lions at Addis Ababa Zoo were not Barbary lions, but rather closely related to wild lions in Chad and Cameroon.[220]

In 1982, the Association of Zoos and Aquariums started a Species Survival Plan for the Asiatic lion to increase its chances of survival. In 1987, it was found that most lions in North American zoos were hybrids between African and Asiatic lions.[221] Breeding programs need to note origins of the participating animals to avoid cross-breeding different subspecies and thus reducing their conservation value.[222] Captive breeding of lions was halted to eliminate individuals of unknown origin and pedigree. Wild-born lions were imported to American zoos from Africa between 1989 and 1995. Breeding was continued in 1998 in the frame of an African lion Species Survival Plan.[223]

About 77% of the captive lions registered in the International Species Information System in 2006 were of unknown origin; these animals might have carried genes that are extinct in the wild and may therefore be important to the maintenance of the overall genetic variability of the lion.[66]

Interactions with humans

In zoos and circuses

Lion at Melbourne Zoo

19th-century etching of a lion tamer in a cage with lions and tigers

Lions are part of a group of exotic animals that have been central to zoo exhibits since the late 18th century. Although many modern zoos are more selective about their exhibits,[224] there are more than 1,000 African and 100 Asiatic lions in zoos and wildlife parks around the world. They are considered an ambassador species and are kept for tourism, education and conservation purposes.[225] Lions can live over twenty years in captivity; for example, three sibling lions at the Honolulu Zoo lived to the age of 22 in 2007.[226][227]

The first European “zoos” spread among noble and royal families in the 13th century, and until the 17th century were called seraglios. At that time, they came to be called menageries, an extension of the cabinet of curiosities. They spread from France and Italy during the Renaissance to the rest of Europe.[228] In England, although the seraglio tradition was less developed, lions were kept at the Tower of London in a seraglio established by King John in the 13th century;[229][230] this was probably stocked with animals from an earlier menagerie started in 1125 by Henry I at his hunting lodge in Woodstock, Oxfordshire, where according to William of Malmesbury lions had been stocked.[231]

Lions were kept in cramped and squalid conditions at London Zoo until a larger lion house with roomier cages was built in the 1870s.[232] Further changes took place in the early 20th century when Carl Hagenbeck designed enclosures with concrete “rocks”, more open space and a moat instead of bars, more closely resembling a natural habitat. Hagenbeck designed lion enclosures for both Melbourne Zoo and Sydney’s Taronga Zoo; although his designs were popular, the use of bars and caged enclosures prevailed in many zoos until the 1960s.[233] In the late 20th century, larger, more natural enclosures and the use of wire mesh or laminated glass instead of lowered dens allowed visitors to come closer than ever to the animals; some attractions such as the Cat Forest/Lion Overlook of Oklahoma City Zoological Park placed the den on ground level, higher than visitors.[234]

Lion taming has been part of both established circuses and individual acts such as Siegfried & Roy. The practice began in the early 19th century by Frenchman Henri Martin and American Isaac Van Amburgh, who both toured widely and whose techniques were copied by a number of followers.[235] Martin composed a pantomime titled Les Lions de Mysore (“the lions of Mysore”), an idea Amburgh quickly borrowed. These acts eclipsed equestrianism acts as the central display of circus shows and entered public consciousness in the early 20th century with cinema. In demonstrating the superiority of human over animal, lion taming served a purpose similar to animal fights of previous centuries.[235] The ultimate proof of a tamer’s dominance and control over a lion is demonstrated by the placing of the tamer’s head in the lion’s mouth. The now-iconic lion tamer’s chair was possibly first used by American Clyde Beatty (1903–1965).[236]

Hunting and games

Main article: Lion hunting

See also: Lion baiting

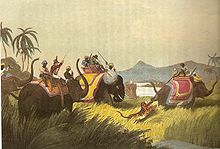

Lion hunting has occurred since ancient times and was often a royal tradition, intended to demonstrate the power of the king over nature. Such hunts took place in a reserved area in front of an audience. The monarch was accompanied by his men and controls were put in place to increase their safety and ease of killing. The earliest surviving record of lion hunting is an ancient Egyptian inscription dated circa 1380 BC that mentions Pharaoh Amenhotep III killing 102 lions in ten years “with his own arrows”. The Assyrian emperor Ashurbanipal had one of his lion hunts depicted on a sequence of Assyrian palace reliefs c. 640 BC, known as the Lion Hunt of Ashurbanipal. Lions were also hunted during the Mughal Empire, where Emperor Jahangir is said to have excelled at it.[237] In Ancient Rome, lions were kept by emperors for hunts, gladiator fights and executions.[238]

The Maasai people have traditionally viewed the killing of lions as a rite of passage. Historically, lions were hunted by individuals, however, due to reduced lion populations, elders discourage solo lion hunts.[239] During the European colonisation of Africa in the 19th century, the hunting of lions was encouraged because they were considered pests and lion skins were sold for £1 each.[240] The widely reproduced imagery of the heroic hunter chasing lions would dominate a large part of the century.[241] Trophy hunting of lions in recent years has been met with controversy, notably with the killing of Cecil the lion in mid-2015.[242]

Man-eating

Further information: Man-eater lions

Lions do not usually hunt humans but some (usually males) seem to seek them out. One well-publicised case is the Tsavo maneaters; in 1898, 28 officially recorded workers building the Uganda Railway were taken by lions over nine months during the construction of a bridge in Kenya.[243] The hunter who killed the lions wrote a book detailing the animals’ predatory behaviour; they were larger than normal and lacked manes, and one seemed to suffer from tooth decay. The infirmity theory, including tooth decay, is not favoured by all researchers; an analysis of teeth and jaws of man-eating lions in museum collections suggests that while tooth decay may explain some incidents, prey depletion in human-dominated areas is a more likely cause of lion predation on humans.[244] Sick or injured animals may be more prone to man-eating but the behaviour is not unusual, nor necessarily aberrant.[245]

Lions’ proclivity for man-eating has been systematically examined. American and Tanzanian scientists report that man-eating behaviour in rural areas of Tanzania increased greatly from 1990 to 2005. At least 563 villagers were attacked and many eaten over this period. The incidents occurred near Selous Game Reserve in Rufiji River and in Lindi Region near the Mozambican border. While the expansion of villages into bush country is one concern, the authors argue conservation policy must mitigate the danger because in this case, conservation contributes directly to human deaths. Cases in Lindi in which lions seize humans from the centres of substantial villages have been documented.[246] Another study of 1,000 people attacked by lions in southern Tanzania between 1988 and 2009 found that the weeks following the full moon, when there was less moonlight, were a strong indicator of increased night-time attacks on people.[247]

According to Robert R. Frump, Mozambican refugees regularly crossing Kruger National Park, South Africa, at night are attacked and eaten by lions. Frump said thousands may have been killed in the decades after apartheid sealed the park and forced refugees to cross the park at night.[248]

Cultural significance

Main article: Cultural depictions of lions

The lion is one of the most widely recognised animal symbols in human culture. It has been extensively depicted in sculptures and paintings, on national flags, and in contemporary films and literature.[44] It is considered to be the ‘King of Beasts’[249] and has symbolised power, royalty and protection.[250] Several leaders have had “lion” in their name including Sundiata Keita of the Mali Empire, who was called “Lion of Mali”,[251] and Richard the Lionheart of England.[252] The male’s mane makes it a particularly recognisable feature and thus has been represented more than the female.[253] Nevertheless, the lioness has also had importance as a guardian.[250]

In sub-Saharan Africa, the lion has been a common character in stories, proverbs and dances, but rarely featured in visual arts.[254] In the Swahili language, the lion is known as simba which also means “aggressive”, “king” and “strong”.[56] In parts of West and East Africa, the lion is associated with healing and provides the connection between seers and the supernatural. In other East African traditions, the lion represents laziness.[255] In much of African folklore, the lion is portrayed as having low intelligence and is easily tricked.[251] In Nubia, the lion-god Apedemak was associated with the flooding of the Nile. In Ancient Egypt, lions were linked both with the sun and the waters of the Nile. Several gods were conceived as being part lion, including the war deities Sekhmet and Maahes, and Tefnut, the goddess of moisture..[256]

The lion was a prominent symbol in ancient Mesopotamia from Sumer up to Assyrian and Babylonian times, where it was strongly associated with kingship.[257] The big cat was a symbol and steed of fertility goddess Inanna.[250] Lions decorate the Processional Way leading to the Ishtar Gate in Babylon which was built by Nebuchadnezzar II in the 6th century BCE. The Lion of Babylon symbolised the power of the king and protection of the land against enemies, but was also invoked for good luck.[258] The constellation Leo the lion was first recognised by the Sumerians around 4,000 years ago and is the fifth sign of the zodiac. In ancient Israel, a lion represented the tribe of Judah.[259] Lions are frequently mentioned in the Bible, notably in the Book of Daniel, in which the eponymous hero is forced to sleep in the lions’ den.[260]

Indo-Persian chroniclers regarded the lion as keeper of order in the realm of animals. The Sanskrit word mrigendra signifies a lion as king of animals.[261] In India, the Lion Capital of Ashoka, erected by Emperor Ashoka in the 3rd century CE, depicts four lions standing back to back. In Hindu mythology, the half-lion Narasimha, an avatar of the deity Vishnu, battles and slays the evil ruler Hiranyakashipu. In Buddhist art, lions are associated with both arhats and bodhisattvas and may be ridden by the Manjushri. Though they were never native to the country, lions have played important roles in Chinese culture. Statues of the beast have guarded the entrances to the imperial palace and many religious shrines. The lion dance has been performed for over a thousand years.[262]

In ancient Greece, the lion is featured in several of Aesop’s fables, notably The Lion and the Mouse. In Greek mythology, the Nemean lion is slain by the hero Heracles who wears its skin. Lancelot and Gawain were also heroes slaying lions in medieval Europe. Lions continue to appear in modern literature such as the Cowardly Lion in L. Frank Baum‘s 1900 The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, and in C. S. Lewis‘s The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe. The lion was portrayed as the ruler of animals in the 1994 Disney animated feature film The Lion King.[263]